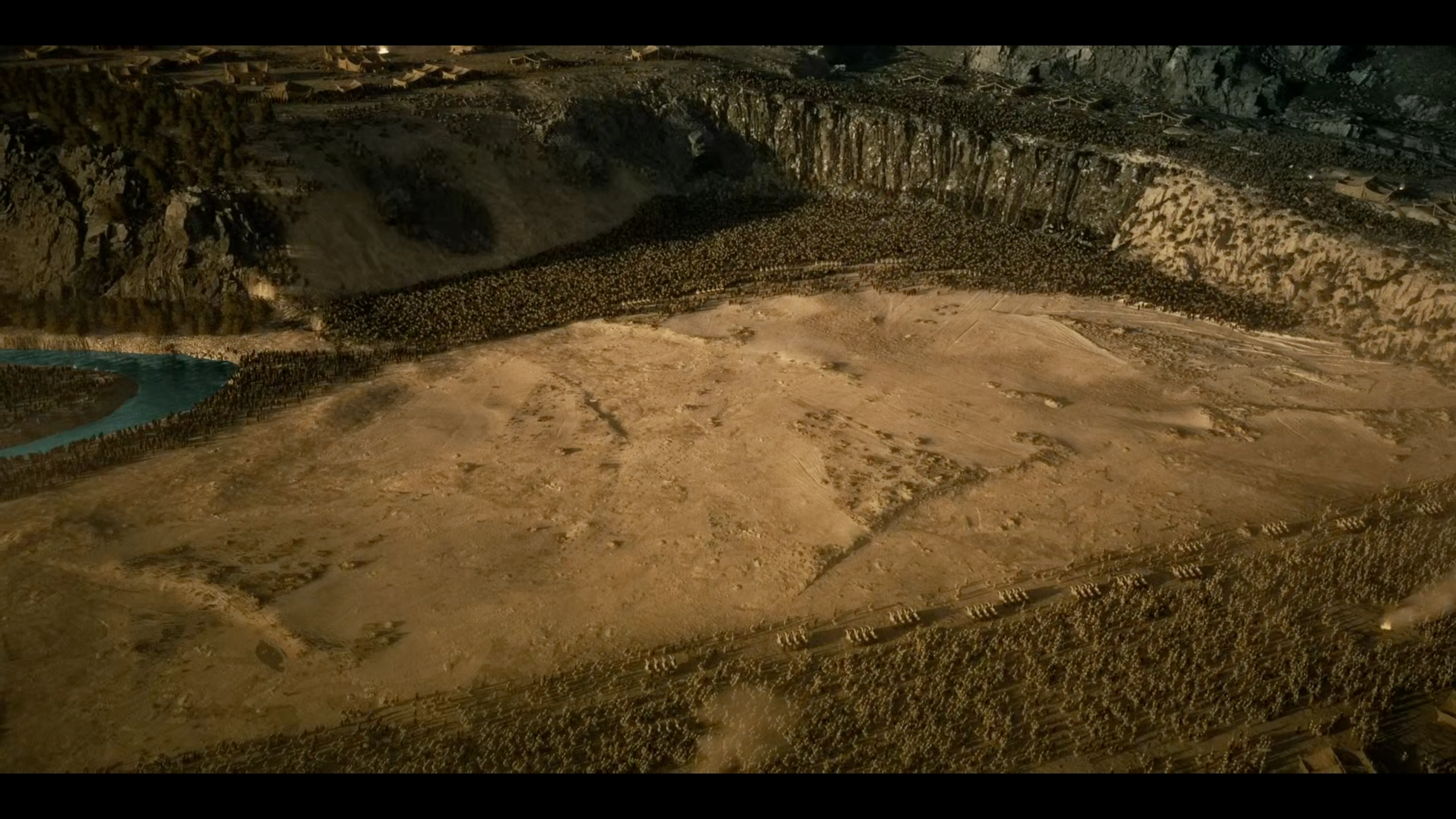

Some time ago I watched House of David. This frame caught my attention.

A battle is about to start, soon to be superseded by the combat between David and Goliath. Two armies facing each other. Classic movie stuff.

One thing I remember from our French officer school's strategy courses is that elevation matters. A lot.

So much so that it's estimated one man uphill will take out three coming from below, and that's with modern weapons. Back then... it must have been, what, 1 to 5?

In the screenshot you can clearly see the armies of Israël went _downhill_ to face the Philistines, giving up their excellent defensive position, literally backing themselves into a corner, especially when outnumbered 3 to 1.

What of it, then, why the nitpicking?

Well, I learned something else, outside army, which cost me much time, effort and cash. I learned good decisions come from good positions. We often obsess over making _the right choice_, rather than improving the position from which we make our decisions over time.

> "You don't need to be smarter than others to outperform them if you can out-position them. Anyone looks like a genius when they're in a good position, and even the smartest person looks like an idiot when they're in a bad one. [...] The company with cash on the balance sheet has nothing but good options to choose from. When bad times come, and they always do, their options go from good to great."

> *— Shane Parrish, Clear Thinking*

The idea isn't exactly new. Take for instance Jean de La Fontaine's fable, "The Cicada and the Ant", or Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger hoarding cash because it gives Berkshire Hathaway "options" (like buying when everyone is busy panic-selling).

In a world where most of us are busy operating in crisis mode, running around putting out fires, some are busy fireproofing. Fewer still — not unlike a distant Marcus Licinius Crassus[^1] — are figuring out how to profit from the ones others allowed to start.

I think success has more to do with staying in the game than being the smartest or toughest in it. A weak spot is a weak spot, as we're reminded with the story of David and Goliath.

A useful habit is asking what could take you out, then focusing on fixing that as soon as humanly possible.

This is what Andrew Grove did with Intel, as he recalls in his book [[Only the Paranoid Survive|Only the Paranoid Survive]].

This is also at the core of the success of Morgan Stanley, where people obsessively maintain 'blue books', a lit of worst-case scenarios that could wipe them out if not addressed.

The worst time to look for a job is when you need one. The worst time to raise funds is when you're all out of cash. The worst place to learn a new language is a country that doesn't speak it. I wonder how many companies were bought by their accounting-savvy competitors during Covid-19.

What good is being smart when all your options suck?

[^1]: Marcus Licinius Crassus created the first fire brigade. Good guy. But instead of putting out fires immediately, he would offer to buy the burning houses from their desperate owners — at ridiculously low prices. If they agreed, he'd put out the fire, rebuild the house and either rent it to its previous owner or resell it at a large profit. Questionable ethics. Allegedly, molten gold was poured down his throat either before or after his death... There's probably a lesson in here somewhere.